The Fresh Produce Industry in Nogales, Arizona: Economic Impacts and Challenges

An Industry with a Long Tradition

In a recent study funded by the Nogales - Santa Cruz County Economic Development Corporation,1 the impact of the importation of fresh produce from Mexico was evaluated in the context of the local economy of Nogales and Santa Cruz County. The import of Mexican fresh produce through Nogales, Arizona’s largest border port of entry, has a long tradition. For more than a century Nogales has served as the main gateway to North American markets for Sinaloa- and Sonora-grown tomatoes, squash, cucumbers, peppers, and other, mostly winter-harvested, vegetables.

Annually, about 120,000 trucks cross the border bringing about $2.5 billion worth of Mexican fresh produce (3-year average). Over time, a true cross-border industry cluster has developed based on intricate business linkages between growers in Sinaloa and Sonora, and distributors/shippers in Arizona.2 In Nogales and Santa Cruz County a number of economic activities have developed around the importation of fresh produce, including customs brokerage services, warehousing and repackaging, shipping/distribution and sale brokerage, and freight forwarding. Whereas the commission fees collected for shipping/distribution and sale brokerage services are the major source of County income associated with the fresh produce imports, about 70 warehouses concentrated along I-19 give the physical landscape a distinctive character.

Industry Definition and Sources of Economic Impacts

In this report, the fresh produce “industry” is defined as encompassing a number of “primary” and “associated” activities. Primary activities are directly involved in importation, warehousing and distribution of Mexican fresh produce to North American and Canadian markets, and in terms of the North American Industry Classification System include: fresh fruit & vegetable merchant wholesale (NAICS 424); agents and brokers engaged in wholesaling (NAICS 425 ), truck transportation (NAICS 484), support activities for transportation including freight forwarders and custom brokers (NAICS 488), and warehousing and storage (NAICS 493). Associated activities bring additional money to the local economy from outside, such as payroll and operational expenses of the federal employees employed with the Customs and Border Protection (CBP), collection of truck crossing fees by the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT), and sale of diesel fuel for transportation from Nogales’ warehouses to final destinations.

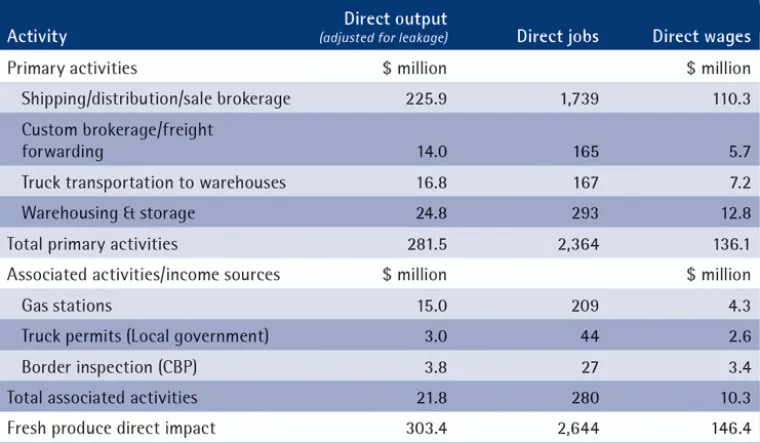

By combining several research methods,3 it is estimated that the primary activities generate $281.5 million, while associated activities generate additional $21.8 million in Santa Cruz County, or a combined $303.4 million annually, after adjusting for leakage.4 A direct job impact is 2,644 jobs, of which 1,739 are in shipping/distribution/sale brokerage sector followed by 293 in warehousing and storage, 209 at gas stations, about 160 providing custom brokerage/freight forwarding services and truck transportation services from the border to warehousing. The direct wage impact is $146.4 million (Table 1).

Table 1: Direct Economic Contribution of Fresh Produce Industry in Santa Cruz County, Arizona

Source: Estimates of “Output” are based on a combination of information from interviews with industry representatives and data from IMPLAN model of Santa Cruz County; “Adjusted direct output” based on % leakage, “Direct jobs” and “Direct wages” from IMPLAN model. 5

Total Impact on County Jobs, Wages and Output

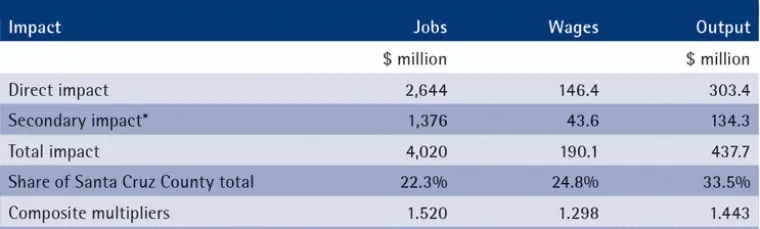

Through ripple effects, the fresh produce industry generates an additional 1,376 jobs and $43.6 million in wages in Santa Cruz County. Combining direct and secondary (indirect and induced) impacts, the industry supports more than 4,000 jobs, generates $190.1million in wages and produces a total monetary impact of $437.7 million (including wages and taxes) in Santa Cruz County (Table 2).

Table 2: Fresh produce industry: direct and secondary impacts in Santa Cruz County

*Combined indirect and induced impacts. Source :IMPLAN model of Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

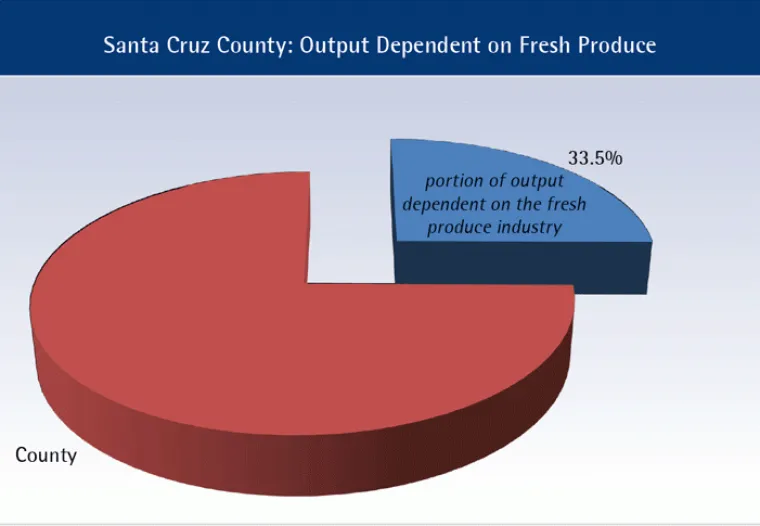

The importance of the fresh produce industry for the economy of Santa Cruz County is reflected in the following numbers: 22.3 percent of all County jobs and 24.8 percent of all wages directly or indirectly depend on the import of Mexican fresh produce; a full one third of the County’s output depends on the fresh produce industry (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Output Dependent on Fresh Produce in Santa Cruz County

*A full one third of the County’s output depends on the fresh produce industry.

In other words, as expressed in the form of multipliers, the fresh produce industry impacts the County’s economy in the following way:6

- Every 100 direct jobs in the fresh produce industry generate an additional 52 jobs elsewhere in the County (job multiplier of 1.520);

- Every $1 in wages to direct employees in the fresh produce industry generates an additional 29 cents in wages in other sectors (wage multiplier of 1.298);

- Every $1 in direct output in the fresh produce industry generates an additional 44 cents in other economic sectors in Santa Cruz County (output multiplier of 1.443).

Linkages with Local Businesses

According to the IMPLAN model, more than 120 local businesses (sectors) directly benefit from the fresh produce industry through purchases of goods and services. The industry spends $30.6 million7 locally on inputs of various services such as warehousing and storage, couriers and messenger services, business support services, legal services, and automotive equipment rental. Major manufacturing inputs – forklifts and packaging materials – are not produced in the County, but imported from manufacturers in Phoenix and Yuma through their retail representatives in Nogales. Close to $47 million leaks out of the County for purchases of goods and services not available locally.

Industry Needs and Challenges

An on-line survey of members of the Fresh Produce Association of the Americas provided a glimpse into industry needs and challenges. The three top needs are related to workforce improvement, including increased demand for higher education, better computer skills and better technical skills. This reflects the fact that warehousing, packaging and distribution technology has changed involving more automation and computerization than it did in the past. On the other hand, one of the unchanged characteristics of the fresh produce industry -- as it relates to the workforce -- is its seasonal character. Although the season for some vegetables has expanded thanks to greenhouse use, the importation and distribution of fresh produce is still concentrated in winter months from October through May, which creates traditionally high unemployment during summer months.

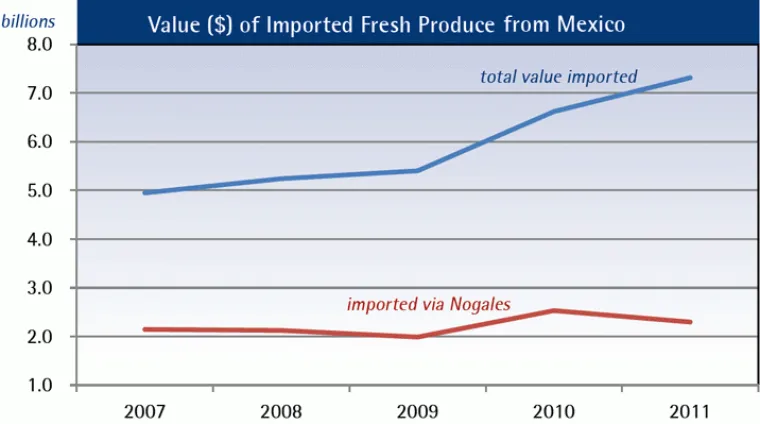

Although the value of imported Mexican agricultural products through Nogales doubled between 2002 and 2011 from $1.26 billion in 2002 to $2.53 billion in 2011, the import of Mexican fresh produce through Arizona BPOE was lagging behind a general trend. The value of all U.S. imports of agricultural products from Mexico increased 110% compared to a 38% increase through Nogales in the same period 2004-2011 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dollar Value of Imported Fresh Produce From Mexico

*The value of all U.S. imports of agricultural products from Mexico increased 110% compared to a 38% increase through Nogales in the same period 2004-2011.

There are several possible reasons for this trend and challenges facing the Nogales fresh produce industry. Texas BPOE, most notably Hidalgo (with adjacent McAllen and the expanding Pharr border crossing) have been increasing their share of Mexican fresh produce partly due to growing agricultural production in central Mexico and partly due to border port infrastructure, including inspection services and crossing wait times. Geography also plays a role in shipments destined for U.S. east coast markets as Texas BPOE offer the shortest distance.

There is also a continuing competition with Florida tomato growers. Tomatoes comprise about 23 percent of total fresh produce imports through Nogales and thus any continuing dispute with Florida tomato growers potentially affects the volume and shipping price of the Nogales fresh produce industry.8

*Eller College of Management, Economic & Business Research Center and School of Geography and Development

**Department of Agricultural & Resource Economics

Notes:

1Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi and Gary D. Thompson, “Bi-national Business Linkages Associated with Fresh Produce and Production-Sharing: Foundations and Opportunities for Nogales and Santa Cruz County,” June 2013, prepared for the Nogales - Santa Cruz County Economic Development Corporation by the University of Arizona Eller College and Department of Agricultural and Resources Economics. Funded by EDA Grant 2012, the study constitutes Phase One of the Nogales Innovation Partnership Project (NIPP). Available at http://ebr.eller.arizona.edu and www.nogalescdc.com.

2V. Pavlakovich-Kochi, A.H. Charney, A.C. Vias and A. Weister, Fresh Produce Industry in Nogales, Arizona: Impacts of a Transborder Production Complex on the Economy of Arizona, An Economic and Revenue Impact Analysis. The University of Arizona: Office of Economic Development. Prepared for The City of Nogales, Arizona, 1997. Available at http://ebr.eller.arizona.edu.

3Combination of an analysis of data on import value of fresh produce, interviews with industry representatives regarding commissions, and data contained in the IMPLAN input-output model of Santa Cruz County.

4Adjusted for “leakage” from the local economy through purchases of goods and services that are not produced locally.

5IMPLAN (Impact M for Planning) is a widely used modeling system originally developed by USDA Forest Service, now operated by the Minnesota IMPLAN Group (MIG). It is based on input-output methodology that traces how economic sectors in a regional (state or county) economy are interconnected through purchases and sales of products and services. Based on these relationships, the model traces how any change in one part of the economy ripples across the entire economy.

6A multiplier is obtained by dividing the total impact by direct impact.

7These are estimates of indirect impacts (i.e., inter-business purchases of goods and services) obtained via IMPLAN model for Santa Cruz County.

8See for example Arizona State University’s Tim Richards’ analysis; also T. Karts, “Florida, FPAA exchange salvos in tomato dispute,” The Packer, 1/24/2013.